Typical Wieght Gain for Newborn Cystic Fibrosis Babies

- Research commodity

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Factors affecting the growth of infants diagnosed with cystic fibrosis by newborn screening

BMC Pediatrics book 19, Commodity number:356 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Newborn screening (NBS) for cystic fibrosis (CF) improves nutritional outcomes. Despite early dietetic intervention some children fail to grow optimally. Nosotros study growth from birth to two years in a cohort of children diagnosed with CF past NBS and identify the variables that influence future growth.

Methods

One hundred forty-four children were diagnosed with CF by the Due west Midlands Regional NBS laboratory between November 2007 and October 2014. All anthropometric measurements and microbiology results from the first 2 years were collated as was demographic and CF screening data. Classification modelling was used to place the fundamental variables in determining future growth.

Results

Complete data were bachelor on 129 children. 113 (88%) were pancreatic insufficient (PI) and 16 (12%) pancreatic sufficient (PS). Mean birth weight (z score) was iii.17 kg (− 0.32). At that place was no significant divergence in birth weight (z score) betwixt PI and PS babies: 3.15 kg (− 0.36) vs 3.28 kg (− 0.05); p = 0.33. Past the first dispensary visit the difference was significant: 3.42 kg (− 1.39) vs 4.sixty kg (− 0.48); p < 0.0001. Weight and height remained lower in PI infants in the first yr of life. In the get-go 2 years of life, 18 (14%) infants failed to regain their nascence weight z score. The median time to achieve a weight z score of − 2, − 1 and 0 was 18, 33 and 65 weeks respectively. The median times to reach the same z scores for height were 30, 51 and ninety weeks. Birth weight z score, change in weight z score from birth to first clinic, faecal elastase, isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, isolation of Staphylococcus aureus and sweat chloride were the variables identified by the classification models to predict weight and height in the first and second year of life.

Conclusions

Babies with CF have a lower birth weight than the healthy population. For those diagnosed with CF past NBS, the weight difference between PI and PS babies was non significantly different at nativity but became so past the get-go clinic visit. The presence of certain factors, most already identifiable at the get-go clinic visit can be used to identify baby at increased risk of poor growth.

Background

The implementation of newborn screening (NBS) has fundamentally changed the care of children with cystic fibrosis (CF) [1]. They are now identified in the get-go few weeks of life and no longer have to look for the presenting symptoms to become astringent enough to warrant investigation [ii]. Historically, this look was oftentimes associated with failure to thrive and irreversible lung damage [3]. CF-NBS improves outcomes, especially nutritional ones [four, v]. This is important for children with CF as nutritional condition is closely related to lung part, quality of life and ultimately survival [half dozen]. The nutritional benefits of CF-NBS are maintained into machismo [7].

Despite early on diagnosis and the initiation of advisable handling, some infants diagnosed with CF by NBS do not attain optimal growth [8]. Antenatal factors such as maternal smoking or poor diet can contribute to this, as can postnatal factors such every bit acute or chronic respiratory infections, adherence with therapy, nutritional intake, dose of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy and other environmental exposures [9, 10]. Information technology would be useful for clinicians to know which variables take the most significant touch on on babe growth. This would mean children at higher gamble of growth failure could be identified and considered for more careful monitoring of growth and/or earlier nutritional support. We collated NBS, demographic, microbiology and growth data on a accomplice of children diagnosed with CF by NBS. We so used nomenclature modelling to plant the factors / variables useful in predicting infant growth.

Method

Study population

A cohort of 144 children diagnosed with CF by NBS was identified. This included all babies with a positive CF NBS from the West Midlands Regional Screening Laboratory betwixt 1st Nov 2007 and 31st October 2014 who had a confirmed diagnosis of CF (identification of two CF-causing mutations and/or a sweat chloride ≥threescore mmol/L). V children categorized as Cystic Fibrosis Screen Positive Inconclusive Diagnosis (CF SPID) [11] were excluded. Two children had died and two moved out of expanse. A further six patients were excluded due to incomplete datasets. The remaining 129 children attended ane of the 2 tertiary CF centres in the region: Birmingham Children's Hospital and Purple Stoke University Hospital. Although these ii centres work independently, both follow the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland CF Trust and European CF Order Standards of care resulting in like clinical practices [12, 13].

Data collection

Demographic and newborn screening data were collected. These included date of diagnosis (taken as date of commencement clinic visit or date of diagnosis of meconium ileus), gender, ethnicity, nascence weight, the presence of meconium ileus, mean immunoreactive trypsinogen, CFTR mutations, sweat chloride, faecal elastase (measured at outset clinic appointment), weight at starting time clinic visit and mode of feeding (sectional breast / exclusive formula / mixed). All weight and length measurements recorded in the kickoff 2 years of life were then collated. Bereft information points were available for head circumference to allow meaningful analysis. We too recorded age at outset isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. These data were obtained from the West Midlands NBS Laboratory database, patient's clinical notes and the electronic results systems at the 2 CF Centres. All height and weight measurements were converted into z scores using the WHO-UK anthropometric calculator. This corrects for sex activity and gestational age. To summarise growth, the following four outcomes were calculated for each kid: hateful weight z score in first yr of life, mean weight z score in 2nd year of life, mean pinnacle z score in the offset yr of life and mean height z score in 2nd yr of life. The median time for children to accomplish meridian and weight z scores of − two, − 1 and 0 was calculated and children who did non regain their nativity weight z score in the first 2 years of life were identified.

Classification modelling to identifying variables affecting growth from 0 to 2 years

Before classification modelling could be undertaken, the accomplice had to be validated using a clustering algorithm (k-means) [xiv]. This ensured it was representative of the UK CF population. The anthropometric measurements as well every bit the demographic, newborn screening and microbiology data were included every bit inputs and the mathematically generated clusters were scrutinised by the CF clinicians (Physician, WC and FG) to ensure they corresponded to clinical phenotypes. Decision-tree classification models were and then generated to determine the variables that predicted future growth. Inputs were the demographic, newborn screening and infection variables. The model analyses all the inputs merely only uses those with predictive event in the decision trees. The iv outcomes were the mean z scores for meridian and weight in the commencement and second year of life. These outputs were chosen every bit the z scores oft varied significantly over time meaning a z score from a single time indicate would not have been representative. Each classification model was validated using a stratified 5-fold cross-validation method. This approach is used when the sample size does not let for a representative split (such as 70% / xxx%) for model training and validation sets. The data is split up into five sets ensuring each set up has proportional representation of all classes in each fix. Modelling is repeated five times each using a different 5th of the data for validation. The final model reported is the one obtained using all the data, nonetheless, the error reported is the mean error out of the v repeats.

Results

Patient demographics

The sample included 63 (49%) girls and 66 (51%) boys. Hateful (SD) gestation historic period was 38.9 (1.8) weeks with viii (6%) born < 37 weeks gestation. Twenty i (16%) children had meconium ileus. Median (IQR) age at diagnosis was 22 (17–25) days. This was afterward in pancreatic sufficient (PS) compared to pancreatic insufficient (PI) babies: 25.5 (21.v–32) vs 20 (16–25), p = 0.004. 121/129 (94%) children were Caucasian and 8/129 (6%) were Asian, Afro-Caribbean or other white. 68/129 (53%) were homozygous and 122/129 (95%) heterozygous for the Phe508del variant.

Diet and result of pancreatic role

The mean (SD) birth weight of the entire cohort was 3.17 (0.51) kg giving a mean (SD) z score of − 0.32 (1.13). The mean (SD) birth weight was 3.21 (0.50) kg for boys and 3.12 (0.53) kg for girls. The mean (SD) birth weight z scores were − 0.35 (1.07) for boys and − 0.30 (1.20) for girls. Using a faecal elastase cut-off of 200 μg/thou, 113 (88%) children were PI and 16 (12%) PS. When reviewed at their first clinic visit, 29 (22%) infants were exclusively breast-fed, 60 (47%) were exclusively formula milk and 40 (31%) were mixed feeding. There was no divergence in mode of feeding between PI and PS. All babies were started on standard treatment on the solar day of diagnosis. The difference in weight between PI and PS infants was non meaning at birth simply became so by the time of the offset clinic visit. Height and weight was significantly lower in PI children in the commencement year of life. The divergence was less in the second twelvemonth and no longer meaning. See Table 1. In the commencement ii years of life, 18 (14%) of infants failed to regain their BW z score, all of these were pancreatic insufficient. The median time for children to achieve a weight z score of − 2, − 1 and 0 was eighteen, 33 and 65 weeks respectively. The median times to reach the same z scores for acme were 30, 51 and 90 weeks.

Microbiology data

All the children were on oral Staphylococcus aureus prophylaxis. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated in sixteen of the 129 children in the beginning two years of life. The median (IQR) historic period of the first isolate was 0.22 (0.08–0.63) years. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was isolated in 45 children in the first 2 years of life. The median (IQR) historic period of the showtime isolate was 1.18 (0.82–1.49) years. All these isolates were non-mucoid. No child met the Leeds Criteria for chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in the first 2 years of life [xv].

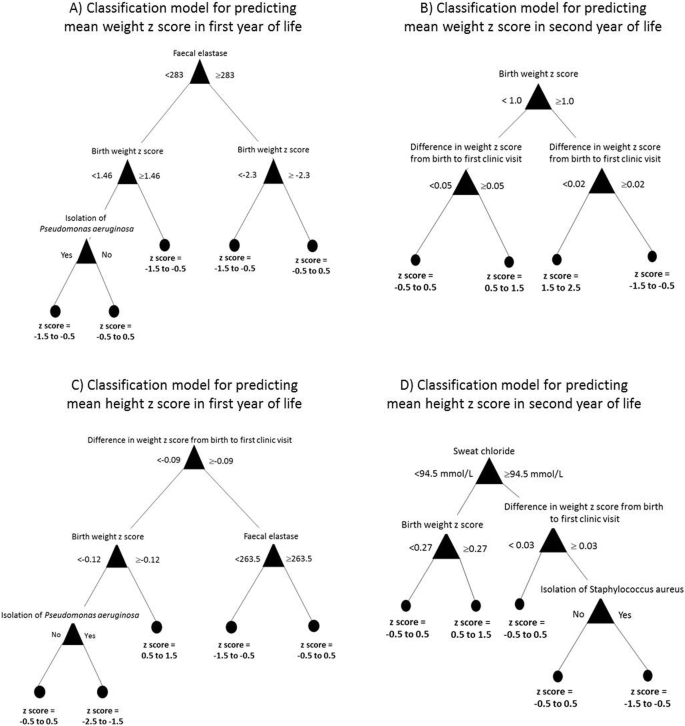

Variables affecting future growth

The unsupervised cluster analysis identified two singled-out groups. See Table two in Appendix. The CF clinicians agreed the clusters were clinically relevant every bit they represented PI and PS phenotypes. This validated the cohort. Decision tree nomenclature modelling was therefore undertaken to identify the variables that could be used to predict the growth outcomes listed higher up. See Fig. one. Across the 4 models, birth weight z score, change in weight z score from birth to first clinic, faecal elastase, isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, isolation of Staphylococcus aureus and sweat chloride were the variables of use in predicting time to come growth. Chiefly, the way of feeding was not identified every bit a predictor of infant growth by whatsoever of the nomenclature models.

Decision tree models generated by classification modelling showing the factors predictive of mean weight and summit z scores in the first and 2nd year of life

Word

This report reports growth from birth to 2 years in a cohort of children diagnosed with CF by NBS. Nomenclature modelling is likewise used to identify the variables affecting infant growth, to our knowledge this it is the get-go fourth dimension this methodology has been used in this grouping.

Previous accomplice studies show CF babies have a lower birth weight than healthy children although it is usually nevertheless inside the normal range [16, 17]. Our cohort follows this pattern with a mean birth weight z scores of − 0.32. The lower nascence weight may relate to gestational age as this was on boilerplate 38.9 weeks. Although the WHO-Britain anthropometric estimator corrects the birth weight z scores for gestational age, it but does this for those < 37 weeks. CFTR may take a role in prenatal growth. As children with PS CF have college remainder CFTR function than PI CF infants, this would be consistent with the observation of lower birth weights in PI infants. This hypothesis requires replication in a larger cohort as the divergence in birth weight between PI and PS infants was not statistically significant. Interestingly the gestation age was very like for PI and PS infants (38.5 versus 38.8 weeks). Infants with CF have been shown to have reduced levels of insulin similar growth gene [18]. This may explain the difference in birth weight between CF and non-CF babies and why some children with well managed CF withal fail to accomplish their growth potential.

Postnatally, pancreatic function has a clear issue with the weight difference between the PS and PI infants becoming statistically significant at the first clinic visit when the child had 'untreated CF' for an average of 22 days. The degree of faltering growth observed in this curt period was one of the about important variables identified past the classification model in predicting infant growth. Therefore, infants who experience the most severe nutritional consequences earlier handling, continue to exercise so subsequently this is started. These infants are likely to be those with mutations associated with the about severe loss of CFTR function. Despite handling with pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, PI infants had a significantly lower height and weight in the first twelvemonth of life than PS infants. This divergence reduced in the 2d year showing grab-upward growth tin can be achieved with prolonged treatment pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy and advisable nutritional back up.

Infants with CF who are PI are more likely to take lower weight and top z scores than those who are PS [16]. Information technology is therefore unsurprising that faecal elastase is ane of the variables used past the classification models to predict hereafter growth. PI infants usually have at least one grade I, II or III mutation which are associated with college sweat chloride which explains its inclusion in some of the models. Chronic infection with PA has an adverse issue on nutritional parameters in children with CF [17]. In our study, a single isolation of PA was linked with reduced infant weight and summit. It is possible this was a direct issue of the PA infection or more probable that children who isolate PA accept more significant lung disease which affects growth. The effects of acute and chronic SA infection on the growth of children in CF is not well known merely early on infection, peculiarly occurring as a co-infection with other organisms, may be associated with severe lung illness which would affect growth [nineteen, 20].

The importance of birth weight in predicting time to come growth is well established in the salubrious children. The GECKO Drenthe Nascency Cohort included 2447 healthy infants and identified nascency weight and style of feeding as the near important factors at predicting growth in the first vi months of life [18]. The classification modelling in our study did not identify style of feeding equally a factor predictive of future growth although the sample size may accept been too pocket-size to identify this. Early nutritional condition is a central predictor of time to come health in children with CF [20]. It is therefore unsurprising that CF children with low birth weight have increased pulmonary affliction in after babyhood [17]. Increasing the birth weight of children with CF would therefore have long term wellness benefits. This could only be achieved through general public wellness measures targeting all pregnant mothers as it is unusual for the diagnosis of CF to be fabricated prenatally.

Our report has several limitations. As nosotros did not have a matched control group of non-CF infants from the same area we relied on the WHO-Britain anthropometric computer to generate z scores merely accept this may miss local variations. There are potentially a huge number of variables that could affect infant growth. Due to the retrospective nature of this study we were limited as to which factors we could collect data on. Relevant variables which we were unable to collect data on included: parental height and weight, maternal smoking status, maternal diet during pregnancy, pulmonary exacerbations, treatment regimen, nutritional support, adherence with handling and socioeconomic status. All of these may affect infant growth [9]. We used mean z scores over the start and second years of life for superlative and weight as our result for the statistical modelling. We accept this approach lacks granularity but the wide variation seen in the individual measurements it gave us the most useful summary outcome. We considered using alternative growth indices calculated from the weight and height measurements. Still, the WHO does not recommend using BMI for historic period in children under ii years and as per centum weight-for-summit is non independent of the raw data it would have made the modelling results difficult to interpret.

Conclusion

This accomplice study confirms children with CF accept a lower birth weight than not-CF babies. The event of pancreatic insufficiency on weight was not significant at nativity but became so past the showtime clinic visit and remained and then for the first year of life. A number of CF babies did non regain their birth weight z score by two years of historic period. Identification of predictors of poor babe growth such equally low birth weight and poor weight gain from birth to first dispensary should enable focused interventions by clinicians and dieticians to optimise nutritional outcomes. The possible effect of CFTR on antenatal growth and the role of other factors such as adherence to handling and socioeconomic status on infant growth warrants farther investigation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are bachelor from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CF SPID:

-

Cystic fibrosis screen positive inconclusive diagnosis

- CF:

-

Cystic fibrosis

- CFTR:

-

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NBS:

-

Newborn screening

- PI:

-

Pancreatic bereft

- PS:

-

Pancreatic sufficient

- SD:

-

Standard departure

References

-

Castellani C, Massie J, Sontag M, Southern KW. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:653–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00053-9.

-

Lim MTC, Wallis C, Toll JF, Carr SB, Chavasse RJ, Shankar A, et al. Diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in London and south E England earlier and after the introduction of newborn screening. Arch Dis Kid. 2014;99:197–202. https://doi.org/ten.1136/archdischild-2013-304766.

-

Farrell PM, Li Z, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Green CG, Collins J, et al. Bronchopulmonary affliction in children with cystic fibrosis subsequently early or delayed diagnosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1100–viii. https://doi.org/ten.1164/rccm.200303-434OC.

-

Farrell PM, Lai HJ, Li Z, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Greenish CG, et al. Bear witness on improved outcomes with early on diagnosis of cystic fibrosis through neonatal screening: plenty is enough! J Pediatr. 2005;147:S30–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.012.

-

Dijk FN, McKay K, Barzi F, Gaskin KJ, Fitzgerald DA. Improved survival in cystic fibrosis patients diagnosed past newborn screening compared to a historical cohort from the same centre. Arch Dis Child. 2011:1118–23. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2011-300449.

-

Corey M, McLaughlin FJ, Williams Yard, Levison H. A comparing of survival, growth, and pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis in Boston and Toronto. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:583–91.

-

Balfour-Lynn IM. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: evidence for benefit. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:7–ten. https://doi.org/x.1136/adc.2007.115832.

-

Lai HJ, Shoff SM, Farrell PM, Wisconsin Cystic Fibrosis Neonatal Screening Group. Recovery of birth weight z score within ii years of diagnosis is positively associated with pulmonary condition at vi years of age in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2009;123:714–22. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3089.

-

Ong KKL, Preece MA, Emmett PM, Ahmed ML, Dunger DB, ALSPAC Study Squad. Size at birth and early childhood growth in relation to maternal smoking, parity and baby breast-feeding: longitudinal nativity cohort study and analysis. Pediatr Res. 2002;52:863–7. https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200212000-00009.

-

Leung DH, Heltshe SL, Borowitz D, Gelfond D, Kloster M, Heubi JE, et al. Furnishings of diagnosis by newborn screening for cystic fibrosis on weight and length in the first year of life. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:546–54. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0206.

-

Munck A, Mayell SJ, Winters V, Shawcross A, Derichs N, Parad R, et al. Cystic Fibrosis Screen Positive, Inconclusive Diagnosis (CFSPID): A new designation and management recommendations for infants with an inconclusive diagnosis following newborn screening. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2015;14:ane–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2015.01.001 European Cystic Fibrosis Society.

-

Kerem Due east, Conway South, Elborn Due south, Heijerman H. Standards of intendance for patients with cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2005;4:7–26. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.jcf.2004.12.002.

-

The CF Trust'south Standards of Care and Clinical Accreditation Group. Standards for the Clinical Care of Children and Adults with Cystic Fibrosis in the UK. 2001. www.cftrust.org.uk

-

MacQueen J. Some methods for nomenclature and assay of multivariate observations. Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Statistics. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1967;ane:281–97. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.bsmsp/1200512992.

-

Lee TWR, Brownlee KG, Conway SP, Denton K, Littlewood JM. Evaluation of a new definition for chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis patients. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2003;2:29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569-1993(02)00141-viii.

-

Singh VK, Schwarzenberg SJ. Pancreatic insufficiency in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2017;xvi(Suppl ii):S70–8. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.jcf.2017.06.011.

-

Pamukcu A, Bush A, Buchdahl R. Effects of pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization on lung office and anthropometric variables in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1995;19:10–5.

-

Rogan MP, Reznikov LR, Pezzulo AA, Gansemer ND, Samuel M, Prather RS, et al. Pigs and humans with cystic fibrosis have reduced insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) levels at nascency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20571–5. https://doi.org/ten.1073/pnas.1015281107.

-

Hurley MN. Staphylococcus aureus in cystic fibrosis: problem bug or an innocent eyewitness? Breathe. 2018;fourteen:87–ninety. https://doi.org/x.1183/20734735.014718.

-

Junge S, Görlich D, den Reijer M, Wiedemann B, Tümmler B, Ellemunter H, et al. Factors associated with worse lung function in cystic fibrosis patients with persistent Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Ane. 2016;11. https://doi.org/ten.1371/periodical.pone.0166220.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sue Bell (Paediatric CF Dietician at Royal Stoke University Hospital) and Carolyn Patchell (Paediatric CF Dietician at Birmingham Children'south Hospital) for their assistance in collecting the anthropometric measurements. Nosotros would also similar to thank Philippa Goddard and Mary Anne Preece for their assistance in obtaining the NBS Data.

Funding

No funding was secured for this study.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

KP collated and analysed information, wrote the initial manuscript and approved the final version. TK led the computational modelling, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final version. Doc and WC contributed to study blueprint, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final version. FG conceptualized and designed the study, rewrote the first draft of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors approved the concluding manuscript as submitted and agree to exist accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Ideals approving and consent to participate

Upstanding approval was obtained from the South Central - Oxford C Research Ethics Committee (REC Reference xvi/SC/0489).

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

FG is an associate editor of BMC Pediatrics. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original writer(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patterson, Chiliad.D., Kyriacou, T., Desai, M. et al. Factors affecting the growth of infants diagnosed with cystic fibrosis by newborn screening. BMC Pediatr 19, 356 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1727-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1727-9

Source: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-019-1727-9

0 Response to "Typical Wieght Gain for Newborn Cystic Fibrosis Babies"

Post a Comment